What might a Coop Uber look like? (or should we be thinking bigger)?

Given Uber's ability – in spite of owning no cars and employing no drivers – to swiftly grow and dominate any market it enters, there's understandably a lot of interest in a driver-owned Coop competitor, not least amidst growing controversies and opposition. In this article, two coop structures are explored, as well as a third, more open and decentralised protocol option.

I learnt of an interesting coop recently: the Depository Trust & Clearing Corporation, responsible for clearing and settling most US securities (i.e shares & derivatives). At the heart of global neoliberalism is this user-owned coop, holding some $40 trillion in securities and running a service the entire economy depends on. I’d already been surprised enough to learn that Slaughter & May, the leading corporate law firm repping half of the FTSE100, was a mutual partnership with no hierarchy or even boss, amongst hundreds of profit-sharing partners.

If the temples of capitalism embrace user- and worker- owned structures, then why not the digital world? There’s understandably already a lot of interest in the idea of a Coop Uber. As Mike Konczal pointed out last year, Uber is rare in that the assets that make up the company’s service are owned by the workers:

“Given that the workers already own all the capital in the form of their cars, why aren’t they collecting all the profits? Worker cooperatives are difficult to start when there’s massive capital needed up front, or when it’s necessary to coordinate a lot of different types of workers. But, as we’ve already shown, that’s not the case with Uber.”

Uber takes 20% for connecting drivers with passengers, potentially a significant chunk of the estimated $50bn/year generating global taxi industry. In January I looked at how Uber's success was in providing a better interface for both drivers and users, but of course interfaces are considerably cheap to build than fleets of cars or offices. Cory Doctorow backed an Uber Coop at this summer’s FooCamp, tweeting:

Uber's not a charity. If it can't provide more value than its drivers could provide for themselves, it deserves to be disrupted #foocamp

— Cory Doctorow (@doctorow) August 1, 2015

The issue is relevant across the digital economy where certain sectors have, as Justin Fox on Bloomberg says “a tendency toward natural monopoly; as you attract more people to your platform, it becomes more valuable”.

Services who benefit from large databases – be it the most drivers, songs or people’s stuff for sale – will inevitably end up dominated by the service with the most or best records in the database. Network effects dictates that the biggest gets bigger, and there are few ideas about what to do about it beyond accepting it as an operating condition of Web 2.

Fox concluded that “it is possible to imagine that years down the road, when these marketplaces are mature businesses, there might be advantages to running many of them as cooperatives instead of as shareholder-owned for-profit corporations”. Coops are one of those strange semi-socialist structures that fits comfortably within capitalism, yet runs closer to the Catholic economic theory of distributism. Already some taxi firms are shifting: in Denver, where a driver-owned taxi coop of 250 members was formed in 2009, another is on its way with over 1000 members.

Post-Kickstarter, it’s easy to picture a writer-owned Kindle or a filmmaker owned YouTube — being funded and supported by sufficient numbers of disgruntled writers or filmmakers to power it into life. With the rise in ‘worker-on-demand’ applications coops could be a way to offset regular criticism about how these services reduce worker rights.

But for now it’s challenge enough to try to picture what a coop Uber might look like, which is the question I’ve spent some of my spare moments this summer considering. In this long read, after outlining two relatively conventional coop structures, I explore a third option that has more in common with the web and decentralised systems such as Bitcoin.

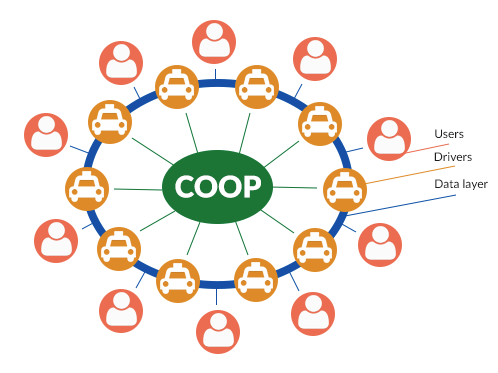

Option 1. The mega-coop

A logical starting point is simply to recreate Uber/Lyft/Halo/etc, with their global network of offices, drivers, marketing and technical infrastructure, as a driver-owned coop, operating either non-profit or with its profits distributed amongst drivers. It would need to be a large, well financed organisation with a legal and customer service team in every country it operated in.

A logical starting point is simply to recreate Uber/Lyft/Halo/etc, with their global network of offices, drivers, marketing and technical infrastructure, as a driver-owned coop, operating either non-profit or with its profits distributed amongst drivers. It would need to be a large, well financed organisation with a legal and customer service team in every country it operated in.

This would need a financing model that dealt with the initial startup investment, the growth funding and the ongoing day-to-day costs. The startup costs could potentially be raised through crowdfunding, or with a community share offering, such as those offered on MicroGenius, so that backers could get a return on their investment. Given Uber has raised a sizeable $7bn across 12 rounds the amount of capital needed would be considerable, while balancing the potential demands of investors against the needs of a democratic member-owner organisation, would be key. Day to day costs could be covered, as with Uber, through a percentage on fares, through monthly/annual membership fees, through licensing API access to external providers, or some combination.

Although costly to setup, a single-coop competitor is appealing because it would be easier to manage, brand and offer users and drivers quality assurance. It would require a commonly agreed-upon set of regulations and pricing, which every taxi would have to follow, so as a democratic organisation would need to find ways to agree pricing and rules across national and regional differences between its members.

Internal voting and localised rules could mitigate some of this, but given the scale such a service would need to expand to have any hope of competing against Uber, the democratic aspects of the organisation may well need to come secondary to the initial growth strategy. Indeed there are no successful giant digital democratic coops working on an Uber scale of 160,000+ drivers to hold as an example. The coop would have to find the right balance between the risks of being so democratic it was slow or unresponsive, against being an unaccountable and top-down behemoth. And, of course, if a success it could still end up with monopoly power, and the ability to force users and drivers to follow a one-size-fits all set of rules.

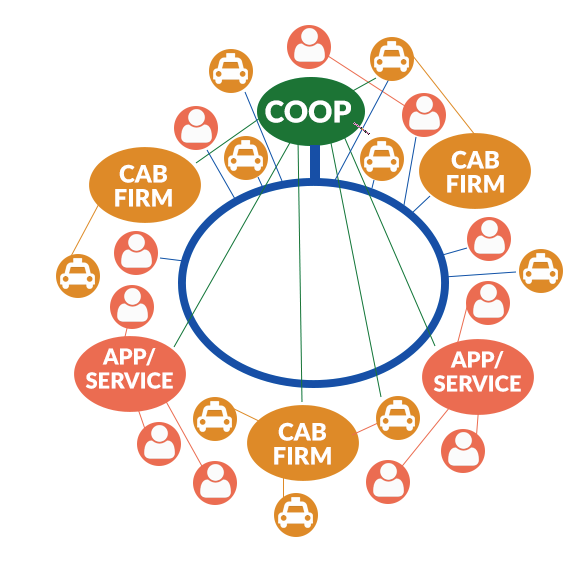

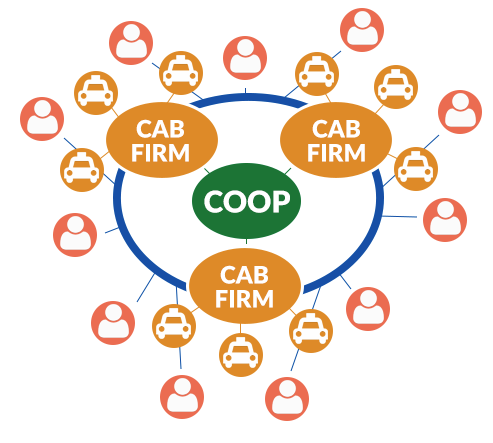

Option 2. Federation of existing companies

Another, lower-cost approach would be a coop that produced software and services for existing taxi companies who already have offices, relationships with drivers and passengers, and often leasing agreements and insurance schemes around their fleet of cars. This would both distribute control out beyond the central coop, responsible for creating software, and work to build upon an existing networks, brands and services, rather than striving to throw them all out of business.

The coop in this instance would produce ‘white label’ software to manage drivers and payments for each of the companies, and also a single branded app which the user downloads. At this point either all the companies in each city and region would need to agree on and use the same prices, or the app would need to indicate that different cars were from different companies and had different prices. By letting each taxi company set their own prices this would create greater potential for competition and variation – car company X with the older cars is 20% cheaper than taxi firm Y which only has recent Sedans, while company Z has a 100% electric fleet of Tesla cars.

The coop in this instance would produce ‘white label’ software to manage drivers and payments for each of the companies, and also a single branded app which the user downloads. At this point either all the companies in each city and region would need to agree on and use the same prices, or the app would need to indicate that different cars were from different companies and had different prices. By letting each taxi company set their own prices this would create greater potential for competition and variation – car company X with the older cars is 20% cheaper than taxi firm Y which only has recent Sedans, while company Z has a 100% electric fleet of Tesla cars.

As well as offering more choice and competition, it also removes from the main coop the burden of verifying and approving new drivers’ identifies or providing customer service. It is closer to an infrastructure, software-as-service company, serving it’s members, who are all established companies. On a simple level, this already exists - a company like Mowares offers an Uber clone from $400. What a coop — owned by all the local taxi companies paying for installs — could further do, is ensure that each install could communicate with each other and produce a single app for users to download that connected them to all of their local taxi companies.

Most appealing about this model is how little cost it would take to achieve scale, provided it was supported by sufficient taxi companies, while also dealing with any potential legal problem, by passing the problem over to taxi companies who have long operated in the local/national environment.

Nevertheless this approach maintains the middle-man, the taxi company – an extra cost which Uber has removed. Part of Uber’s ability to charge low fares is replacing the expense of taxi offices, switchboards and phone receptions with software, reducing the cost of journeys. So this coop model may always end up more expensive than Uber or Lift as it needs to pay both driver, the coop producing the software/service and the taxi companies representing the driver. While some companies, such as executive car services, with account management, may offer sufficient value to justify the added cost, it’s hard to imagine the cost-conscious end of the market acting in the same way. It may require, as Seth Ackerman proposed, cities and countries making a legal requirement for taxi-apps to be worker-owned to succeed.

Of course this is also no help for the driver who, for whatever reason, doesn’t want to join the local taxi-company, or can’t, which may be an issue in areas where there is only one taxi service. But a service which lets drivers register directly has a much greater administrative burden and legal liability around verifying drivers and their licensed vehicles. To do the verification job well, the model ends up more centralised and much closer to the first option above.

Interlude: trustiness as a sliding variable

All that I’ve read and my thinking for most of the summer seems to move between these two models - either a large centralised coop that verifies individuals who join up but that risks being undemocratic and less nimble and innovative; or a more decentralised, federated system that only works with companies who in turn take responsibility for driver management and verification.

Hitchhiking was – and in many places still is – normal, despite there being no identity checks and the occasional, mostly fictional horror story. Because of this it’s something both the driver and passenger do at their own risk, with their eyes wide open — somewhat like giving your credit card details to a website in the 90s. By comparison, a system that records you as a person getting into a specific car, licensed to another specific person at a particular time and location, is many orders of magnitude safer than hitch-hiking. Lift sharing and car-pooling websites have far softer requirements than paid-services – liftshare.com seeks only a verified email address to offer and cost-share a trip you are making – but there are no publicised problems with car-sharing scams.

In other words, perhaps trust is something relative to time, circumstance and conditions. If I’m stuck at night in a remote rural location having missed the last bus - I’d hop in a car with almost anyone if it’s the only one nearby. If it turns out that someone in my office block is making almost the same trip to work each day, even tho I don’t know them I’d be happy to share a ride and split the petrol. If I need to get from a train station to a meeting at the last minute, then I’d want a driver who knows how to handle the city in rush hour.

So, maybe trust is a design challenge as much as a service issue: rather than create a service with a 'guaranteed leve' of security, you could create a service with varying levels that the user is made well aware of. Then, instead of than having apps and coops for different forms of car sharing, you could design and build an architecture – a set of protocols and systems – for car journeys, and build the coop app on top.

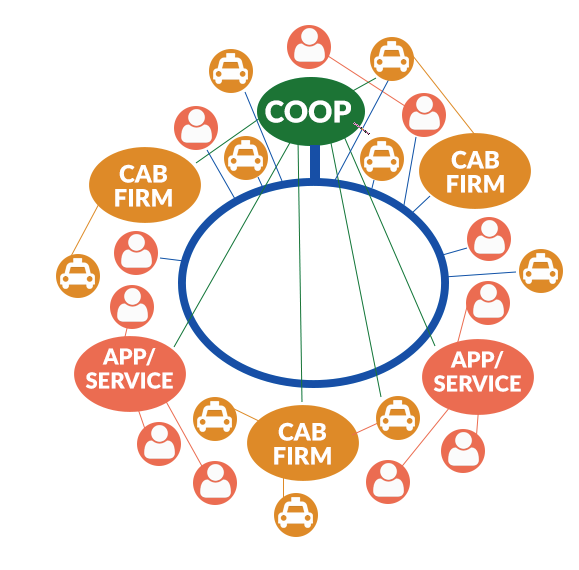

Option 3. A distributed architecture for journey data

It's the far-out idea: and it may be easiest to explain the idea by looking at the web, which illustrates well how much a decentralised, open system with lots of competition at every level can achieve.

It's the far-out idea: and it may be easiest to explain the idea by looking at the web, which illustrates well how much a decentralised, open system with lots of competition at every level can achieve.

URLs are unique, point to websites and are either encrypted, with a certified level of encryption and a https:// prefix, or are unencrypted (http://). These websites can run a huge choice of software and sit on many types of servers; competing search engines can all index these websites and serve up the results through browsers which are viewed by the end user across phones, PCs, tablets, TVs and so on. There’s a total, genuine free-market in devices, browsers, search engines, websites, servers, the software that runs on servers - and this potential anarchy of decentralised maximum-competition is all held together by a commonly agreed naming system pointing to every site (the URLs), and some open source code - HTML, javascript, CSS and HTTP - that everything across the system can understand.

A protocol for journeys, rather than pages, could achieve something similar.

Any driver with a car that wants to offer lifts could be identified with a unique URL: mydonutrickshaw.car or 123.456.789.101112. Maybe they paid for a security certificate to verify their identity and driving/taxi license, so they are a ‘secure’ https-like URL, or maybe they didn’t but they're a friend of a friend.

Someone wanting a lift fires up an app with their phone. It’s already got their preferences stored - they’ll take any lift from Facebook friends, people in their address book, or who work in their company - as well as drivers from Addison Lee, Uber, Lyft, the new Tesla.Coop or any trusted ('https') drivers with a minimum 6 months experience. On telling the app the journey they want to make, they see that there’s an expensive executive car available within five minutes, and a dozen cheaper options in up to 30 minutes, one of whom they’ve travelled with before and liked. If they wait another two hours, there’s a neighbour who will be in the area and will be driving back directly. All this information is pulled from across the system, and all is designed to prevent any single player dominating or monopolising the market through a technical or data monopoly advantage.

How could this work?

This approach has four elements - Coop, Open Source, Register & Semantic data (which, as I drafted this in Dublin airport, I abbreviated as CORS):

- A Coop, funded by its members, in charge of building and maintaining…

- Open Source Software, available to anyone who wishes to use or modify it, provided they register on a…

- Register, a method to provide a trustable, yet decentralised index of all users, drivers, and groupings (i.e. Taxi firms). It could be run on the blockchain, and its records are stored at uniqiue URLS using…

- Semantic data to store information for each URL, unique to each user, driver or group – with access control revealing differing information depending on who is asking, and which any other parts of the system—if allowed—is able to read and interpret meaningfully.

This approach is loosely parallel to the web’s architecture of:

- Worldwide Web Consortium, a non-profit organisation funded by its members to approve…

- HTML/CSS/etc specs, powering websites whose address is stored by…

- ICANN, the global domain name registry, which points to…

- Http web servers, which resolve domain names into working websites, and can be hosted anywhere.

Concepts explained

Semantic data

Semantic Data is a data model pushed forward by Tim Berners Lee shortly before the Web 2.0 explosion. Most sites work by keeping data in a database which pump out the data they’ve been asked for on a page as it is loaded. A semantic page is designed so that all the data can be read on the page as easily as if it was a database (while still looking the same to the end user). This means you don’t need a database that everyone can access to get meaningful, structured information, as long as you can visit the web page, that’s enough.

So, for example, as well as saying, "Buster Keaton was born in Kansas in 1895", the page also contains markup (ie hidden added bits) –

<div typeof="Person"> <span property="name">Buster Keaton</span> was born in <span property="birthplace">Kansas</span> in <span property="birthyear">1895</span> </div>

– so a machine reading it can figure out the age and birthplace of Buster Keaton, without having to log into a central database. Had we adopted Berners-Lee's proposal in our websites from the early 00s we would have a more open, less monopolised web (although only recently has the technology to handle fast concurrent web connections got to a level to make it more viable).

Register / Blockchain

Registers are 'authorative lists you can trust'. If you have a network of semantic pages, be it pages about cars, or songs, or people, you need a method to find them. In this instance, a register is a database or list of all semantic pages. It may contain a name or place and it’s associated url. Anyone in the network who wants to find information can use the register to find the relevent page. This means that database changes happen at a page level (someone changes their address or name), while the register simply adds or deletes entries.

A blockchain is a way of running a register without a central registry. This prevents too much power in the network being in any single point of failure - it offers redundancy that protects against hacking, server downtime, or abuse of hosting power. It works by sharing the work of adding and ammending records in the registry amongst many computers, who each process a small part of the overall workload, often - as with Bitcoin - in return for a payment (a part of a bitcoin). The blockchain is open — it may contain encrypted parts, or point to semantic pages that can only be decrypted with certain permissions – but stores records of additions and changes publicy.

As with the web, certificate authorities could add a further level of trust by granting to drivers a machine-verifiable certificate guaranteeing they are who they say they are.

This model has a few aspects:

- Creation by the coop of the open source software used by both taxis and users is funded by a set of a founder members who will benefit from the service, be it cab companies, taxi-driver unions or individual drivers. Locking-in funding ensures the software is supported and delivered to the needed standard. This could be returnable investment as with a community share offering, or it could be donations or a share of earnings.

- While this coop controls the release of the software and defines the schema or structure of the data people must include - it does not own the network of drivers — anyone publishing a semantic page about their car in the correct format and joining the register/blockchain is in. So without being a member of the coop, say, a taxi company in Delhi could host semantic data (i.e. a page of machine readable information) on each of the cars in its fleet, and as soon as the cars are registered, anyone using the taxi software in Delhi would see these cars in their service.

- Conversely, anyone could build interfaces to read and interact with the data, or integrate it with their service, be it a conference venue wanting to offer taxi-booking from their event aps, or a procurement system trying to pre-book cars at the lowest price. Uber could offer non-Uber cars through it’s app when its own weren’t available, and likewise offer Uber cars through other apps; drivers meanwhile could chose to work through taxi coops and peer-groupings, under a bigger branded umbrella or on their own, keeping the maximum share of the fare.

- Maintenance of the blockchain/register would have a small cost associated with it, which could be paid for either by processing new information added to the blockchain (i.e. in-kind processing across all apps) or a very small payment per transaction. Similarly the core coop would depend on continued funding, which may be through membership fees or a flat, low, levy.

The problems and challenges

Even with this structure there are significant challenges for a distributed system to overcome.

- There's issue of payment: a traditional cash-fare taxi ride stores no details about the passenger or the driver (unless the passenger makes a note of the car registration or taxi license number). Part of ride-apps’ appeal are their cashlessness; for this to work in a decentralised form the user would need to store card details on their own device, uploading the information or making the payment to their driver upon arrival in a dependable, secure way, with some fallback in case their phone lost battery or signal. [NB - 2017 edit: see Dr Richard Stallman's comments with regards this in the comments and his new anonymous but safe digital cash service GNU Taler]

- Would the technology require the driver and user to have the latest phones? How would a cutting edge service address the difference in smart-phone capabilities across the world?

- Privacy and security is fundamental: the driver and passenger would want to keep track of their journeys and how much they had earned or spent on each, but there could be risks if each user’s journey data was stored with the driver, revealing private address and movements to anyone who accessed the driver’s account.

- There's the challenge of building a map of geolocated taxis, sending new coordinates every few seconds. Finding a stable decentralised method to map a stream of ever-changing data such as locations may be more trouble than the cost of paying for a central service to provide that.

- How do you design to clearly indicate different levels of trust/knowledge around different drivers without quantifying drivers down to just numbers? Get this wrong and the end-user is at risk from not knowing if they can trust drivers, and the driver risks being penalised unfairly.

It would be naive to describe these issues as trivial; they aren’t and this doesn’t even begin to cover things like getting sufficient drivers and users to make the system worthwhile — Uber already has a significant first-mover advantage and has spent billions of dollars getting to where it is. Many of the challenges to overcome combine engineering with social/business challenges — which is largely untested waters for many open source communities, although far more normal for cooperatives. An advantage of this is that the coop and open source world each have different yet vital skills and experience to contribute to making something like this happen.

A first step might be to prepare a draft protocol and software proposal and through a series of code-sprints, tele-seminars and conference meetups iron out potential problems and bottlenecks, before forming a multi-stakeholder coop to crowd-fund/crowd-equity a test stack of software. Ideally this would centre around one or two cities, perhaps those which have banned Uber, and to test it at scale with local investment, before trying to roll it out any wider and begin to deal with multi-lingual, multi-currency, multi-legislative environments.

These challenges, tho sizeable, don’t seem insurmountable – this doesn’t seem as complex as landing a robot on an asteroid accelerating through space, while the $50bn+ annual turnover of the global taxi market makes any competitor to a model like Uber, taking up to 20% on every journey, as both credible and fundable.

Indeed the potential rewards for solving this would bring much needed competition to sharing and worker-on-demand space. Imagine a decade or two from now having just one taxi company for the world, or one freelance employment agency, or one letting agency, each with total control over their market, their pricing and worker terms. It would be as if to take the worst parts of totalitarian communism, privatise them and hand over to a single company.

Instead we need an architecture that provides all the benefits of app-based ride-ordering yet maximises competition and – like the web – is open to unlimited participants and new ideas. A decentralised system encourages innovation because the cost of exploring new ideas is far lower and less risky than if it had to take place within a large, cautious corporation or coop. So, if someone finds a way to offer drivers passing takeaway restaurants on the way home extra cash for picking up and dropping of pizza, or to let a business sync their spare vehicle capacity with a same-day delivery service, the architecture would easily accommodate startups around that. If a large UPS-sized shipping company wanted to use the data to forecast when and where roads would be busiest, it could. In other words, the question is less about offering a coop version of Uber as much as using a coop to offer an open, free protocol for car journeys that could run Uber and any number of coops and alternatives sitting on top. It’s a more complex approach, but one that runs closest to the collaborative decentralised network economy and culture we’ve collectively been building this last few decades.

Building a co-op Uber alternative that returned Uber's share of the $$ to riders/drivers is "as hard as making Linux..." #foocamp

— Cory Doctorow (@doctorow) August 1, 2015

Therefore, the existence of GNU/Linux proves that building a co-op, open alternative to Uber is eminently do-able #foocamp

— Cory Doctorow (@doctorow) August 1, 2015

Thanks Dan Gregory, Henry Story & Gordana Halavanja for draft feedback

Addendum 29 Sept 2015: after publishing this some comments alerted me to LaZooz – a community-owned 'decentralised transportation platform' which also uses the blockchain to offer a hybrid lift-share / fee-based car-share. Some articles about it here ('Israel's anti-capitalist, anti-Uber ride-sharing ap just went global'), here ('most important democratising force') and here ('the utopian, hippy Uber').

Addendum 1 Oct 2015: Coop Cabs in Toronto is the city's second biggest taxi operator and a coop and has announced plans to produce a ride-sharring app if the city legislates against Uber. Meanwhile the German Taxi Cooperative is persuing legal proceedings against UberPop.

Addendum 22 September 2017: Arcade City is another coop cab service, decentralised and using blockhain (which loosely replaces the register in option 3 above. They set up in Austin and Manilla after both cities banned Uber.